PFAS - What is that?

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently issued a proposed drinking water limit for 6 PFAS chemicals. The rule is expected to be finalized by the end of 2023. Additionally, EPA also announced plans for wastewater limits of PFAS discharges. That seems like a lot of regulation for something many of us have never heard of.

What is (are?) PFAS?

PFAS doesn’t refer to a single chemical, but rather a group of well over 9,000 human-made chemicals. PFAS is an acronym for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Since the 1940s, this group of chemicals has been used in industrial and consumer products. Note that PFAS is plural.

PFAS are well known for their resistance to water and oils, making them beloved for use in food packaging and preparation materials. Some examples include microwave popcorn bags, pizza boxes, and fast-food containers. Consumer Reports measured PFAS in various restaurant chains. It seems the list of fast-food companies using PFAS in one or more of their containers is much longer than the list of those who have eliminated this class of chemicals from their packaging. In fact, PFAS are so prevalent, it is possible that no company will ever be able to accurately claim their product is “PFAS-free”.

Examples of other PFAS sources are some firefighting foams, water-repellant clothing, cookware, and even dental flosses, though PFAS can be found in many other products. Human wastewater effluent can also be high in PFAS. Once in the environment, PFAS can spread to our drinking water, fish, livestock, crops, and even the air we breathe.

The PFAS Cycle, image courtesy of Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy.

What is the Problem with PFAS?

PFAS are sometimes called “forever chemicals” because they break down very slowly in the environment, if at all. Humans can slowly eliminate PFAS from the body, likely over several years, assuming there is no further exposure. However, many of us and the things we eat (plants or animals) are regularly exposed, potentially causing bioaccumulation of PFAS in the human body. One study even estimated 97% of people in the USA had PFAS in their blood.

The full effects of PFAS on human health are still being examined and studies are ongoing. Some studies, summarized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health, suggest issues with the liver, thyroid, immune system, cholesterol levels, cancer risk, blood pressure, metabolism, birth weight, and fertility. According to the EPA, “health effects associated with exposure to PFAS are difficult to specify for many reasons, such as:

There are thousands of PFAS with potentially varying effects and toxicity levels, yet most studies focus on a limited number of better known PFAS compounds.

People can be exposed to PFAS in different ways and at different stages of their life.

The types and uses of PFAS change over time, which makes it challenging to track and assess how exposure to these chemicals occurs and how they will affect human health.”

What Can We Do?

Finding out if our food or other products have PFAS in them can be difficult. The health department for Madison and Dane County, Wisconsin suggests the following to reduce your exposure:

Check product labels for ingredients that include the words "fluoro" or "perfluoro."

Be aware of packaging for foods that contain grease-repellent coatings. Examples include microwave popcorn bags and fast food wrappers and boxes.

Avoid stain-resistance treatments. Choose furniture and carpets that aren’t marketed as “stain-resistant,” and don’t apply finishing treatments to these or other items. Avoid clothing, luggage, camping, and sport equipment that were treated for water or stain resistance.

Avoid or reduce use of non-stick cookware. Stop using products if non-stick coatings show signs of wear.

PFAS in Drinking Water

Check your Drinking Water

Since 2013 the Missouri Department of Natural Resources has been monitoring public water supplies for four PFAS compounds. You can view the map here.

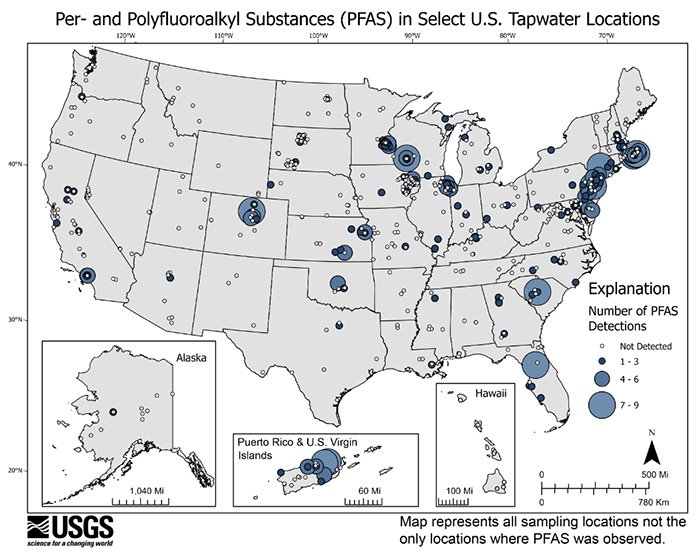

The US Geological Survey recently tested for 32 PFAS compounds in 716 private and public water systems across the US, finding similar results in both.

PFAS in Missouri drinking water, an ongoing survey by the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Click to view the map.

Nationwide PFAS Study by USGS. Click for full size image.