E. coli in the Environment

These bacteria may be growing in your lake!

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a type of bacteria present in the lower intestines of warm-blooded animals. Because warm-blooded animals (including humans) have a lot of E. coli in their bodies, the bacteria are used as an indicator test for the presence of fecal matter (and associated pathogens) in recreational and drinking water. Early work suggested that E. coli could not survive for long outside the host body, making it ideal for this purpose. Essentially, the thought was if E. coli had been found, poop had recently entered the water.

Over the years it has become more apparent that E. coli can survive, and at times even reproduce, in the environment. The result is that the abundance of E. coli may not be related to a recent contamination of the water. In other words, high E. coli concentrations don’t always mean that there is poop in the water.

Salt helps E. coli survive

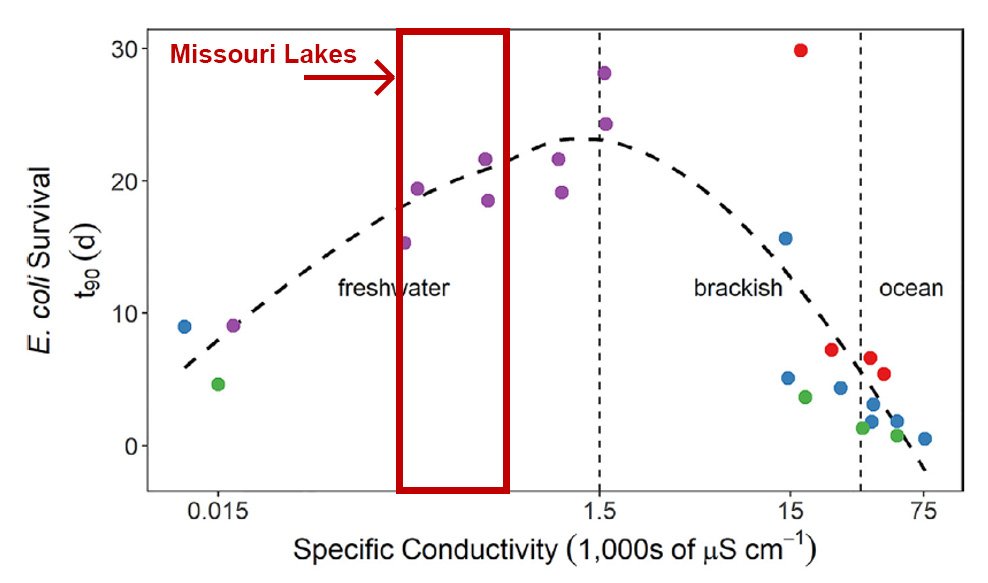

A recent scientific article (2021) suggests that the salinity stream water may be allowing E. coli bacteria to persist longer than previously expected. For our Missouri lakes, adding more salt (like the ones used in fertilizers or industrial runoff) could increase the lifespan of the bacteria even longer.

In naturally salty water (e.g., estuaries and oceans, specific conductivity = 1,500-60,000 µS/cm), E. coli survivability is reduced. As some of our lakes are becoming saltier the assumption was that increasing salt would reduce the ability of E. coli to survive. However, that is not the case according to the study.

Salt, at concentrations lower than found in estuary and ocean water, may provide E. coli with a usable resource that prolongs their life. The study suggests that in streams, where residence time (a measure of how long water “resides” in the water body) is typically 12-20 days, a specific conductivity measurement of 350 µS/cm could result in E. coli surviving for a longer time than in water with either lower or much higher conductivity. Residence time is important as it’s a measure of how quickly the water is replaced (and presumably the E. coli bacteria are washed away). The results of the study suggest that E. coli concentrations could “increase over time even without increases in loading” (contamination).

What about lakes?

The article specifically addressed streams, but we can extrapolate a bit for lakes.

Graph from the study showing the number of days E. coli survive in waters with different conductivity. The conductivity range of most Missouri lakes (red box) added for this article.

The overall average specific conductivity of Missouri lakes places them squarely in the range where E. coli survivability is increasing (see figure above). Adding salt to the lakes will continue to increase the survivability of E. coli, up to about 1,500 uS/cm.

In Missouri, the typical lake residence time is one year, but it can vary depending on factors like lake depth, watershed size, and seasonal rainfall. To state the obvious, lake water stays in the same place longer than stream water. The implication is that E. coli concentrations could increase more in lakes than in streams, even without increased contamination.

Graph showing average conductivity measurements for some Missouri lakes monitored by LMVP.

In summary, among several other undesirable effects, adding salt to our lakes allows E. coli bacteria to live longer lives.

E. coli survivability in beach sand - E. coli at beaches

Not only might E. coli bacteria be surviving longer than previously believed in Missouri lakes, but they may also have taken up residence. Beach sand is well-documented for harboring E. coli. Researchers are working to determine the magic formula in beach sand that is so favorable to E. coli, and it seems moisture content, nutrients, and a carbon source are important.

In one example, two weeks after a Chicago beach’s sand was replaced E. coli recolonized it to previous levels. Concentrations of E. coli were highest in the water and sand near shore (including sand above the water line) and declined dramatically with distance from shore. While birds could have contributed additional bacteria, no other new sources were identified. The authors of the paper suggest that the beach sand is a reservoir for E. coli and may even harbor a reproducing population.

What does this all mean?

If E. coli can persist in the environment outside of a host's gut, then test results, especially at beaches, may consistently show their presence. As a result, some beaches might be closed even in the absence of recent contamination. Perhaps more importantly, if E. coli are around all the time we may not see the effect of new contamination using our current methods. Because of this, the days of using E. coli counts as an indicator may be nearing an end. Recent research suggests that certain genetic characteristics of E. coli are linked to long-term survivability in the environment and other genetic characteristics are linked to human pathogens. Hopefully, someday there will be a simple test capable of differentiating between recently deposited E. coli cells and those that have naturalized, and that test will let us know when human pathogens are present.

Until we have more precise tests, the safest plan is still to stay out of the water if E. coli concentrations are high. Other helpful tips are:

Don’t get lake water in your mouth.

Shower before and after swimming, especially before eating or drinking after a swim.

You can view state park beach testing results from the Missouri Department of Natural Resources at their site: https://dnr.mo.gov/beaches